The Conundrum of the Professional Black Girl

Ever since I was a young girl, I’ve had a fondness for writing and storytelling. In second grade before I went to bed every night, my granny and I would work on whatever books I was writing at the time. She was my illustrator—or as I would say back then my official coloring expert. In third grade I published my first book about my best friend at the time and her adventures with her new dog, Deena.

Naturally, as an avid storyteller, I gravitated towards magazines and their take on long-form narrative storytelling. Essence magazines adorned our living room coffee table and every month I would delve into a beautifully written story complemented with captivating photos of glamorous women who looked like me. As my love and adoration for magazines grew and I broadened my magazine consumption I realized there was something missing from my experience with those different brands. Although I loved the content within their pristinely waxed pages, I didn’t leave my interaction with them fulfilled; I felt like they weren’t talking to me, that the content they created wasn’t meant for me. And in retrospect, in my fully aware self today, I know for a fact that the content wasn’t for me, and these brands made no effort to include me, and girls who looked like me, in their conversations. My curl pattern was never on the spectrum when it came time to rank the best products for each hair type. There was never a list of products for skin care routines that best fit my skin’s level of pigmentation. Yeah, I had been rejected by boys like most young girls in middle and high school, but it wasn’t just because they were immature and didn’t understand girl power. Where were the articles empowering me to overcome rejection because the boys were brainwashed by mainstream media on what was considered beautiful and didn’t like me because I was dark skinned with unrelaxed hair?

Out of the two years I subscribed to Teen Vogue, sometime circa 2006-07 to 2008-09 when they still published 12 issues a year, there were three covers showcasing black women: one of them had three models, Chanel Iman, Jourdan Dunn and another model whose name I don’t remember and the two other covers were Rihanna. I will never forget the feeling I had when I opened those three issues—pure joy. I read them cover to cover. I finally felt like the editors were trying to include women who looked like me in the conversation. Those moments made me realize why I didn’t have a connection with those brands and it was because they weren’t representative of the real world, simply perpetuations of an ideal white American woman and her interests. So, I told my mother to cancel my subscription to Teen Vogue and right then and there I discovered my purpose: to become a feature writer and fight for equal diversity and representation in magazines and media.

I started to fulfill this mission in the summer of 2012 when I came to New York for my first internship at Essence. What an honor it was to actually contribute to the very publication that guided me towards my life’s purpose. The experience, by far, was the most influential thing I’ve ever done in my career. Fortunately for me, the beginning of my career coincided with the beginning of a large push within media for diversity and representation. Black women were speaking up and out against the lack of melanin, extreme levels of cultural appropriation and western European standards of beauty. It was an exciting time. And publications were slowly—emphasis on slowly—but surely responding to the criticism and attempting—emphasis on attempting—to rectify the situation. But as I continued my journey in the life of journalism, my experiences weren’t as wholesome. During my internship at Essence, we were told early on, to not get too comfortable, because this oasis of a place for the young black girl obsessed with working in magazines isn’t the standard for most other publications. We wouldn’t feel as connected, as close to home, as relatable in other places. And it was true. My second internship at the same company but different magazine, I could instantly feel the difference. The feeling was the same as when I went from reading an Essence magazine to reading a Teen Vogue magazine. This place wasn’t for me. This place did not value my experience or my perspective, and in essence did not value me. It was my first real encounter with workplace assimilation, where I really felt the need to choose between my professional advancement and my commitment to my mission and blackness.

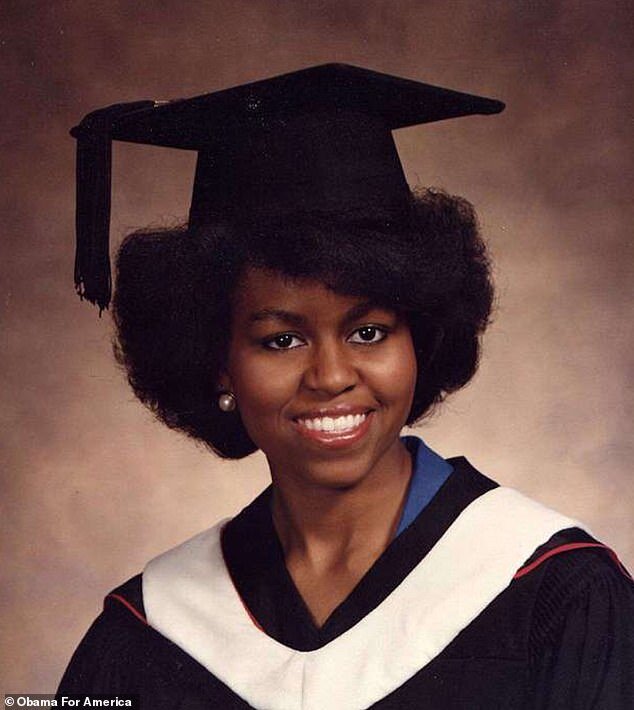

At the time I wasn’t aware this was a common sentiment among black women in all professional industries that warranted scholarly attention, until former lady Michelle Obama’s Princeton thesis became the topic of conversation within certain media circles because of this quote:

“Earlier in my college career, there was no doubt in my mind that as a member of the Black community I was somehow obligated to this community and would utilize all of my present and future resources to benefit this community first and foremost. I have found that at Princeton no matter how liberal and open minded some of my white professors nad classmates try to be towards me, I sometimes feel like a visitor on campus; as if I really don’t belong. Regardless of the circumstances underwhich I interact with Whites at Princeton, it often seems as if, to them, I will always be Black first and a student second.

These experiences have made it apparent to me that the path I have chosen to follow by attending Princeton will likely lead to my further integration and/or assimilation into a White cultural and social structure that will only allow me to remain on the periphery of society; never becoming a full participant.”

This feeling of isolation Michelle speaks of is one many black women and women of color can relate and that is being what Shonda Rhimes referred to in her book Year of Yes, a F.O.D—First. Only. Different. I have several friends working in all types of industries, and they all share one thing in common: they are the few black women working there. Before she found a new job in Miami, my friend was one of two black women in her social media department at an ad agency; my friend, who is now completing her residency for physical therapy at a hospital in Tallahasee, Fla. recently told me there is only one black woman working there other than her; another friend of mine, who works for a prestigious public relations firm in Chicago and D.C., is also the only black woman—actually the only black person—on her team; and another friend of mine who is a writer and takes comedy sketch classes in New York City at UCB laments about how she is the only black woman in those classes.

The same trend occurs in media. More and more women of color began to grace the covers of prestigious and high-esteemed publications. More and more women of color were headlining prime time TV shows and starring in blockbuster and highly acclaimed films, ultimately making them perfect candidates for covers. More and more independent digital media outlets were flourishing, gaining audiences based on the diverse content they produced appealing to people of all backgrounds. The perception of media was that it was changing, it was becoming more diverse. Look! Beyoncé is on the 2016 September cover of Vogue! Women like Melissa Harris Perry, Tamron Hall, Robin Roberts were being hired to anchor major television news shows. But we were fooled by the perception of diversity while these industries continued to remain exclusive when it came to putting the perspectives and existences of women of color central to the publications’ content. So whenever a woman of color or black woman is put on the cover or hired for a hugely influential position in media it becomes a special thing, instead of a normal thing.

For many who have been contributing to scholarship and literature on representation and the lack thereof in mainstream media, the use of buzz words like “diversity” and “representation” were assumed to be synonymous with inclusivity, and unfortunately that turned out not to be the case. No matter how many black women grace the covers of these major magazines, when you flip inside and look at mastheads, or look at the staffs and employee photos of major digital media outlets, there’s very little, if any, representation. Many of these same media outlets appear diverse because of the content they produce, but they are predominantly white. Having one or two black and brown girls on your paid staff doesn’t mean you are inclusive. At worst, a media company might co-opt the language of many black female writers who discuss the black female experience on social media like Twitter. At best, a media company might commission a black girl to write specifically about the black experience, relegating many of us to a lifetime of freelance writing, but they rarely hire black women full time. This says a lot about how they view their company culture and if they see you “fitting in” with that.

Ava DuVernay has constantly talked about the importance of inclusivity in front of and behind the camera. But even with inclusivity, as Michelle points out, in certain settings, there is still a barrier to acceptance for many black women. Regardless of one’s level of education, “respectability”, economic status, pedigree, or ability to pull one’s self “up by their bootstraps”, there is a level or social strata unattainable for black women. Even within industries where black women have predominantly dominated the scene, specifically in music and entertainment, as we witnessed with Beyoncé’s recent Album of the Year Grammy snub for Lemonade, there are still upper echelon institutions that simply refuse to recognize exceptional cultural contributions from black women. As Nicki Minaj commented in her interview with the New York Times about her similar loss when her video for Anaconda was not even nominated for Video of the Year, even though it broke so many records, ‘‘I’m not always confident. Just tired. Black women influence pop culture so much but are rarely rewarded for it.’’

This essay isn’t to say that strides haven’t been made when it comes to diversity and inclusion in the workplace, especially within media. Never in a million years did I think I would ever see a black woman at the helm of Teen Vogue, the very publication I felt excluded from for so long. I think Elaine Welteworth and Phillip Picardi and the rest of the Teen Vogue staff have done an excellent job of establishing a new and inclusive lane of its own to relate to all young women. But that fact shouldn’t overshadow the very real issue of exclusivity present in media. It’s not enough to hire a few minorities from a few marginalized groups and expect the company’s inclusivity quote to be met. Hiring women of color shouldn’t be something of specialty, but should be an act of normalcy. Furthermore, company culture’s need to evolve passed one that expects assimilation, but should encourage a culture of acceptance, and the first way to do that is to not force women to choose between their blackness and their professionalism, but learn how to accept a woman that can do both. And do both well.